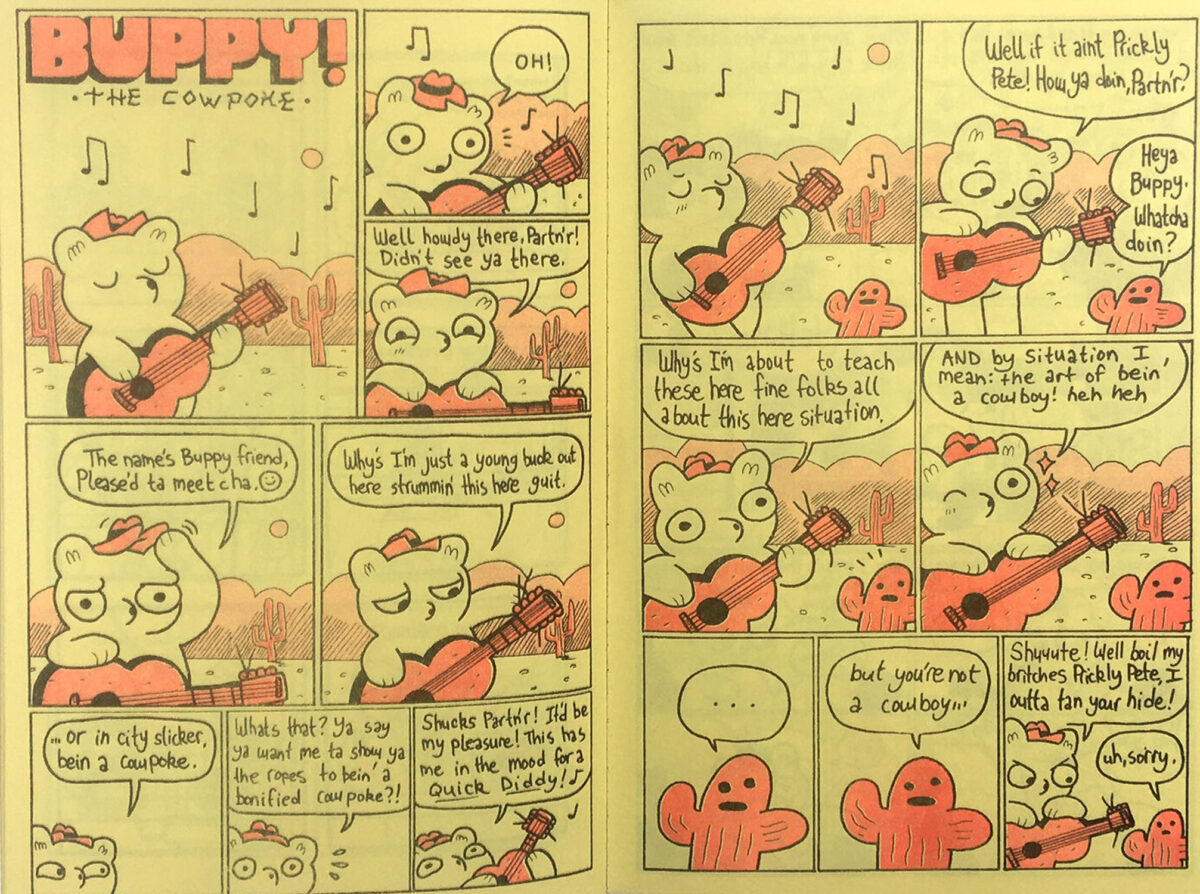

Yu Wei is a visual artist and an independent publisher who is always wandering, reading, drawing, printmaking, photographing, and writing. She makes books and whispers stories through visual approaches. Wei was also a fellow at Spudnik Press from July 2021 to February 2022 and is currently preparing a studio in Beijing to continue her art practice.

Wei was interviewed by Spudnik Press 2022 Spring Intern Andrea Ye. Andrea is pursuing her Bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, concentrating on mix-media drawings and printmaking. Her work addresses the sensorial and sentimental connection with nature.

Andrea Ye (AY): Your website has information about your life and undergraduate experience in Beijing, China. I’m actually also born in China. Can you share something about how you started as an artist in China?

Yu Wei (YW): I went to a middle school in China where we focused on art a lot. After graduating, it was very natural that I go to an art school in China for undergrad and continue it here in Chicago. I studied graphic design for my undergraduate degree and came to Chicago to study at the SAIC Visual Communication Design department.

AY: How does your life in these two art schools compare?

YW: In China, I was more focused on myself and my own personal art practice. I didn’t have much collaborative work during my undergrad, except for a few group projects. The Visual Communication department at SAIC has a different vibe from that of other departments. Other graduate students all have studio cubes, but our department has this kind of office setting. Because of the pandemic, many people went back to their homes so there were only two of us in that studio and we worked together a lot. I also took a lot of courses from printmedia and that was very interesting, because you always work in the print shop. It’s different from just sitting in front of the laptop.

AY: What class did you take in printmedia? Any particular medium?

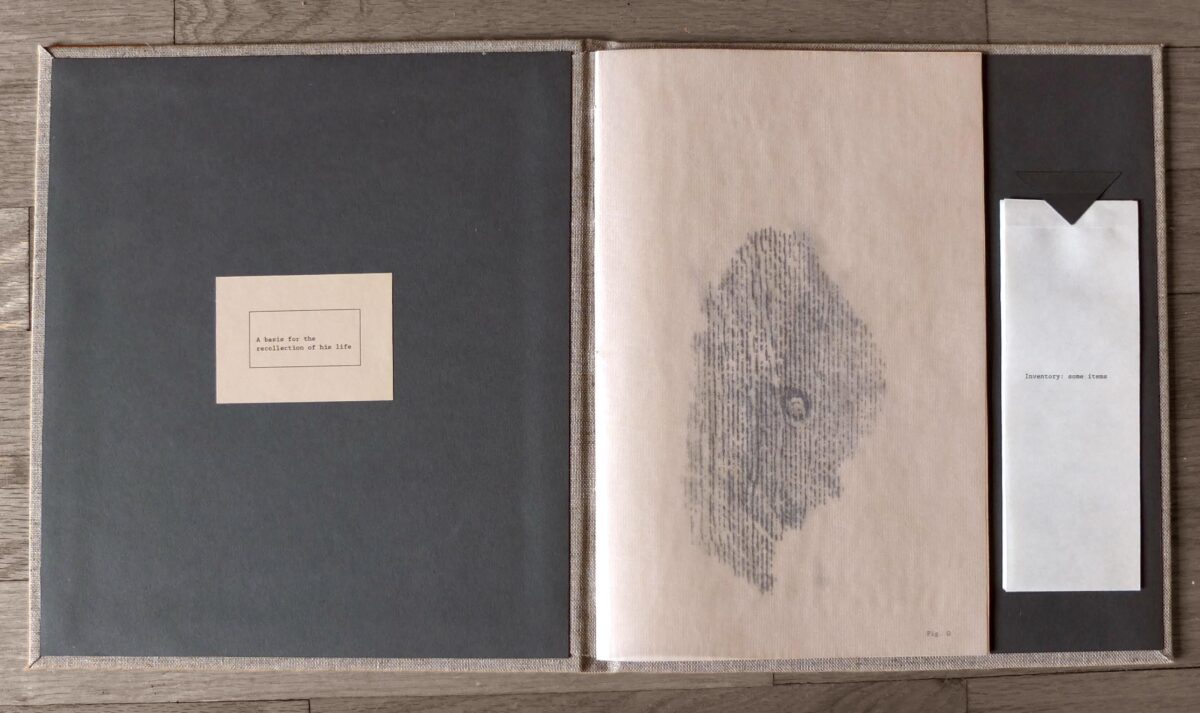

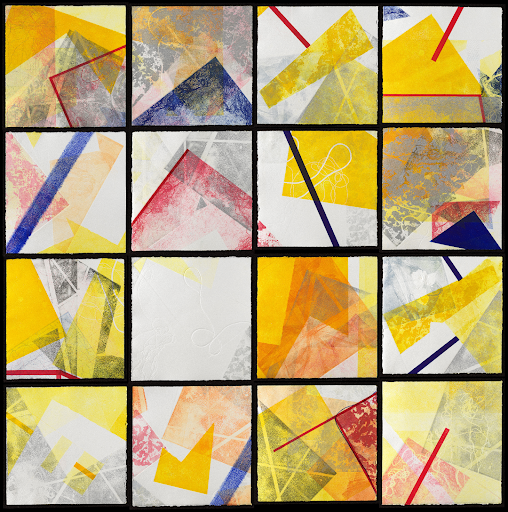

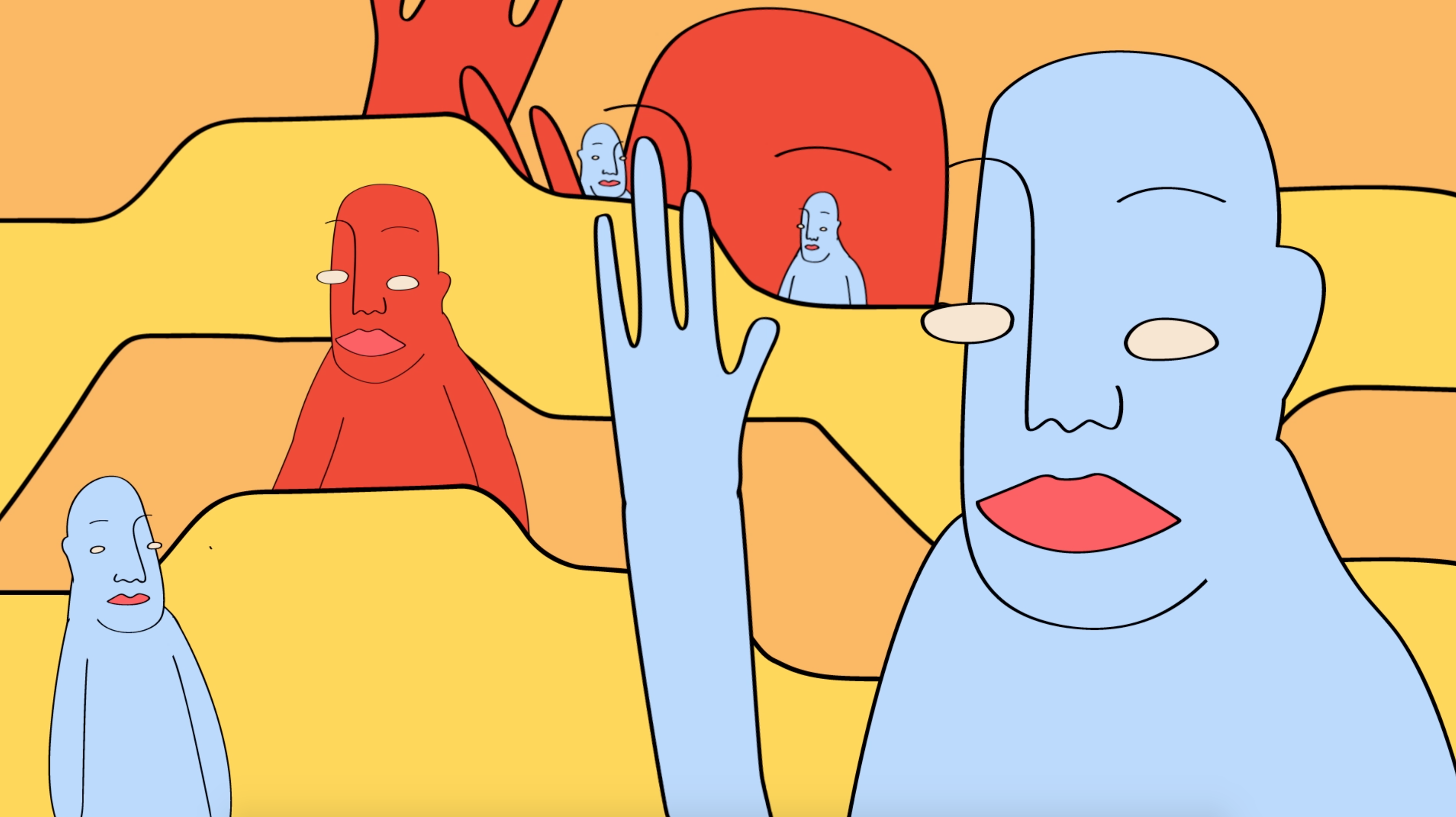

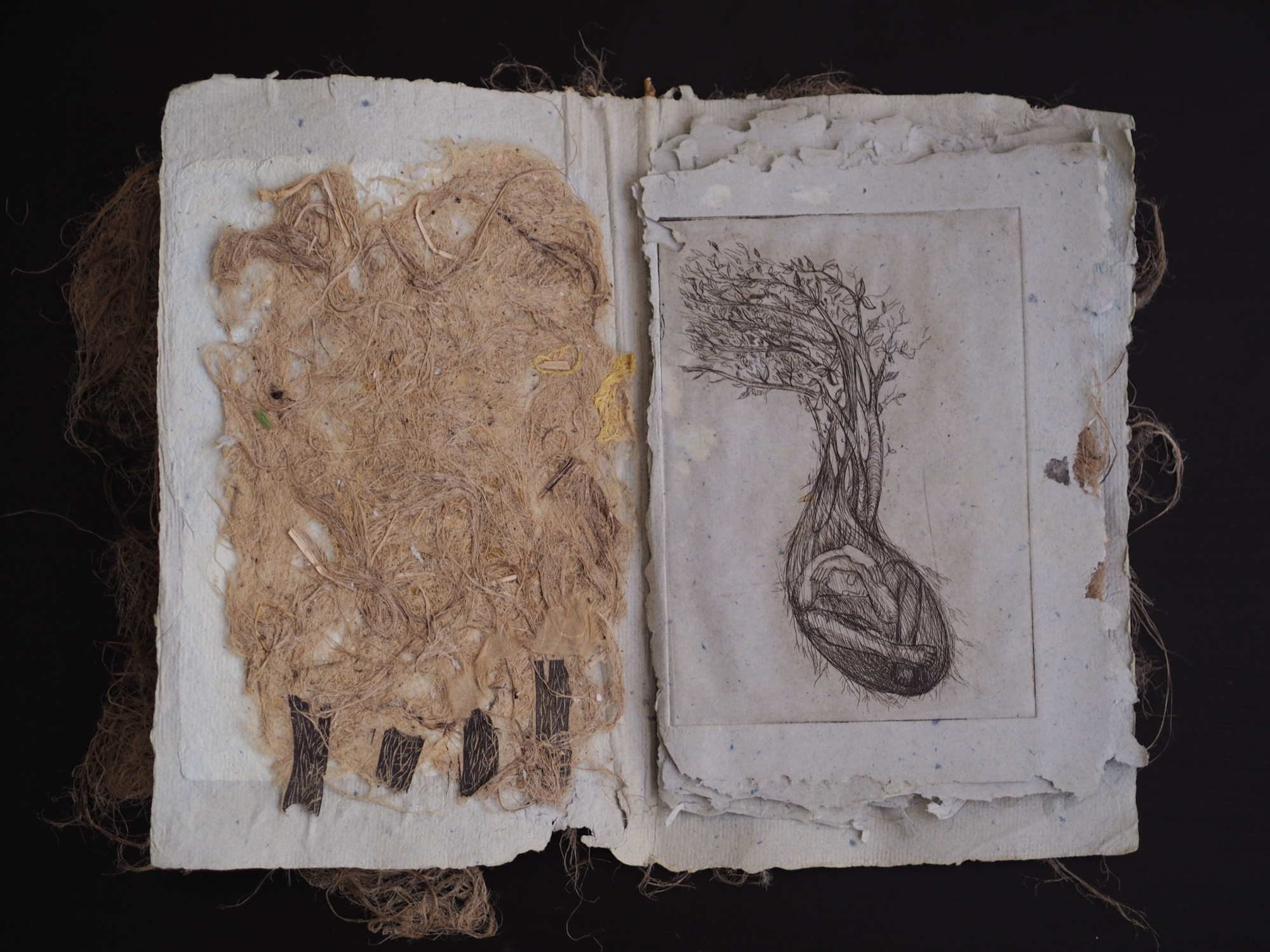

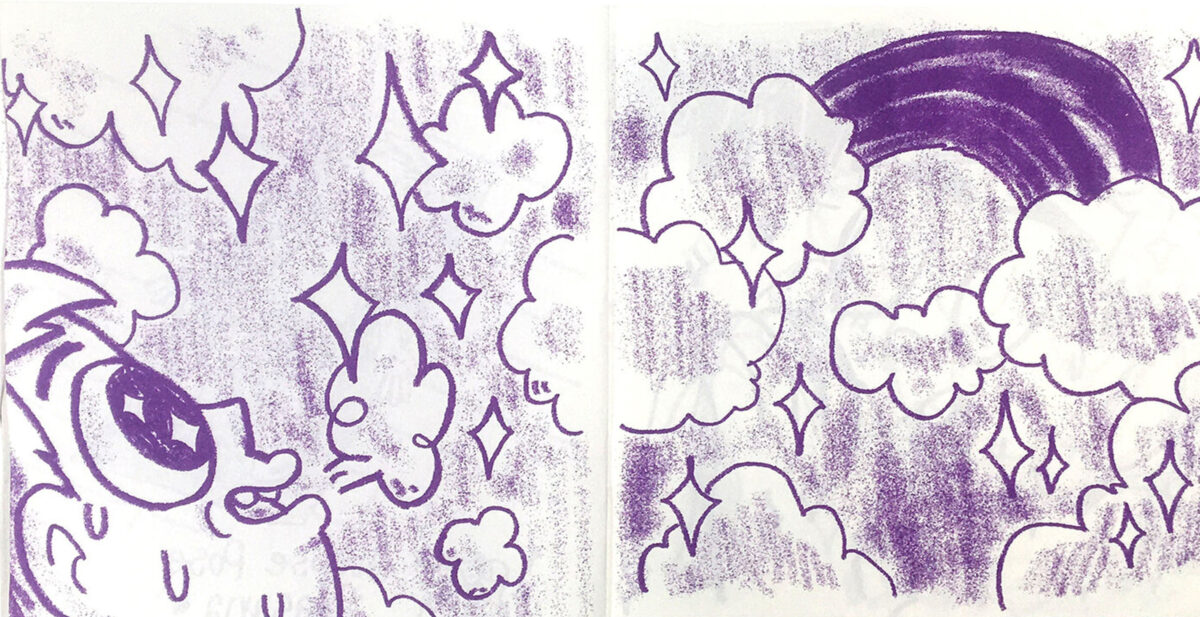

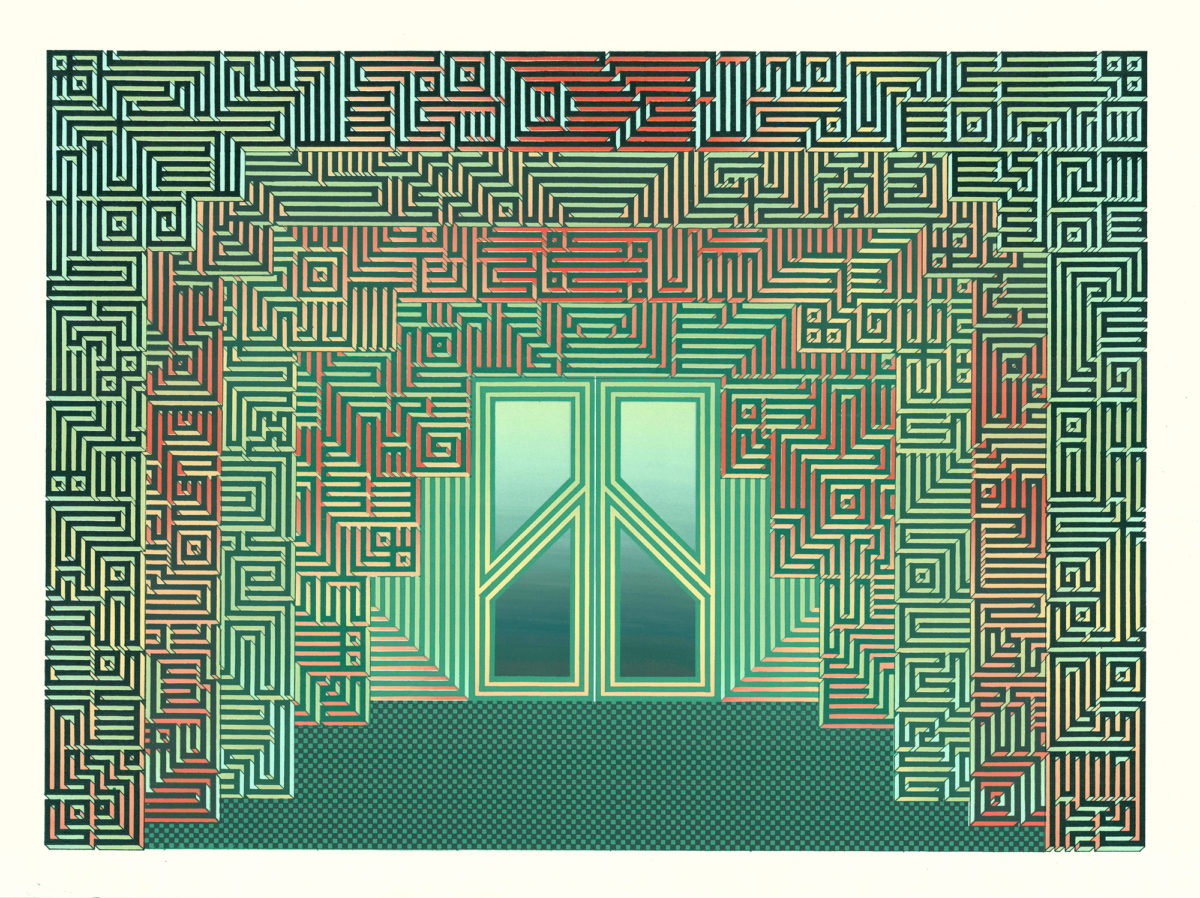

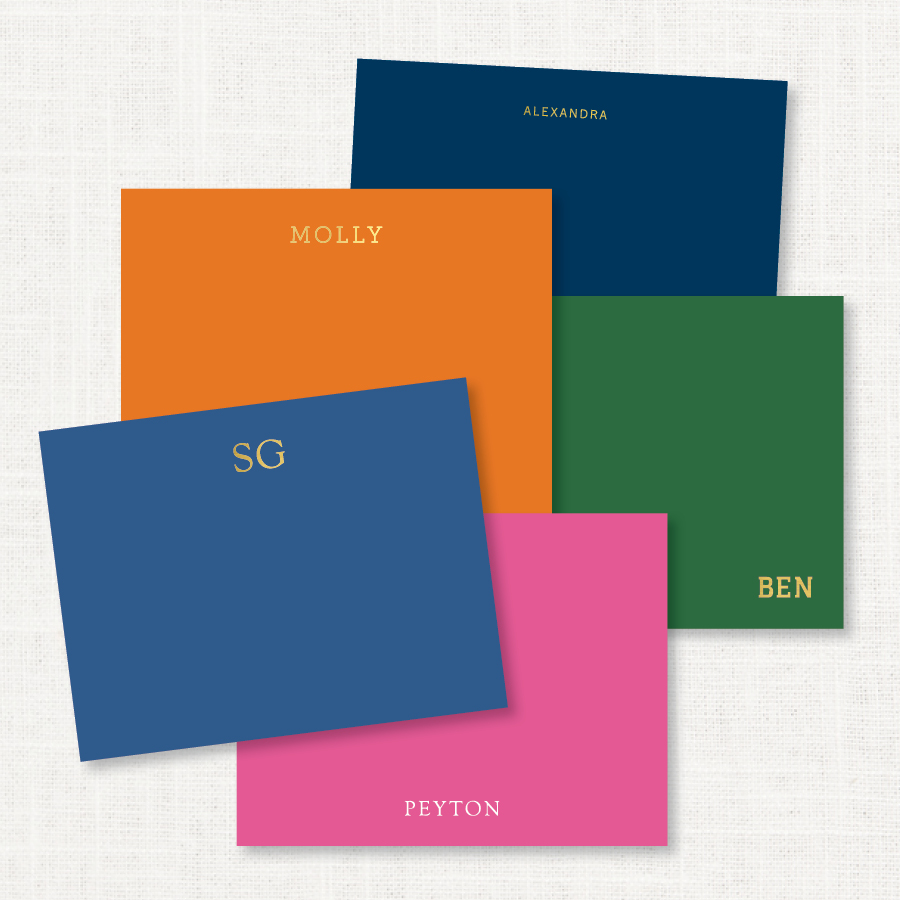

YW: I work a lot with risography because I make books. The first class I took is called “Adventures in Self-publishing.” That’s where I began to know about the system of self-publishing. And this is one of the books I made with risography (see Image 1)

AY: Can you talk about the process and your inspiration?

YW: Do you have a lot of dreams? What kind of dreams? Is it more related to life in reality, or if it is more weird and bizarre?

AY: I would say most of them have connections with real life. I dream about real people but they kind of weave into some surreal scenes and strange plots.

YW: I used to have dreams connected to real life. Basically, it’s like a reverse version of my day. But during the pandemic, when there were around two months that I just stayed in my apartment, I started to have weird dreams that are totally different from the dreams that I used to have. They’re like adventures. Sometimes I wake up and feel exhausted.

AY: Sometimes I wake up and wonder if a dream is actually another world and I just got back from there.

YW: Yeah, I feel that, too. What is real and what is not real is kind of ambiguous. When I have dreams that feel like I’m about to die, I will wake up and realize that maybe I just died in that world and came back to reality. I never had these kinds of dreams before the pandemic, and it is quite surprising personally, so I made a book about them.

Image 1: “What adventure down there awaits its end?”, 2020 riso-printed book, 8 x 10 inches

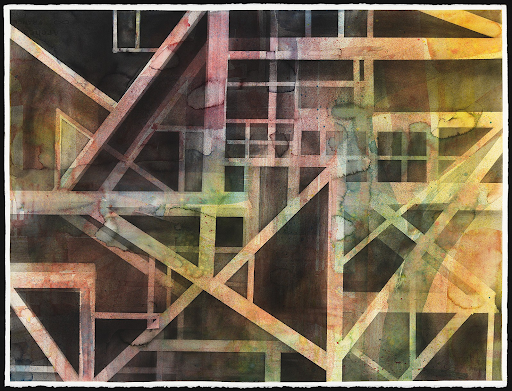

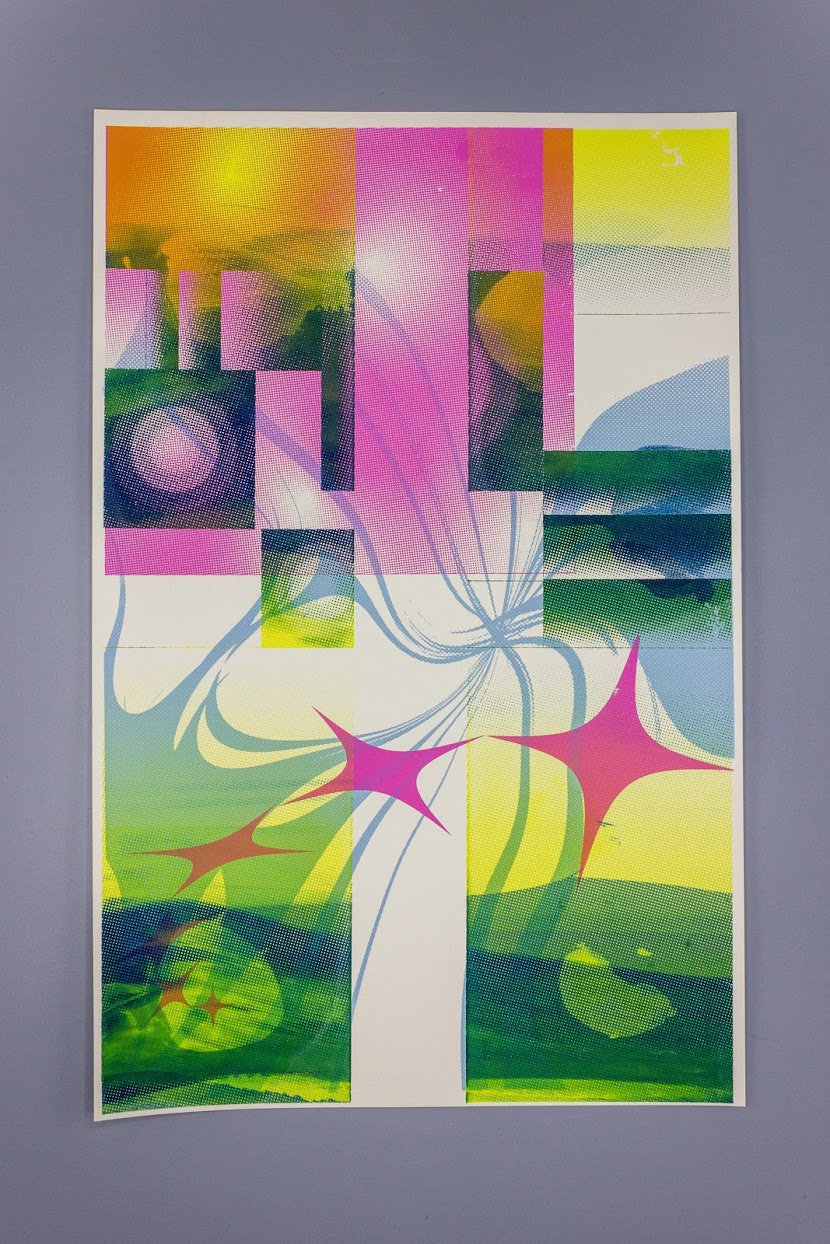

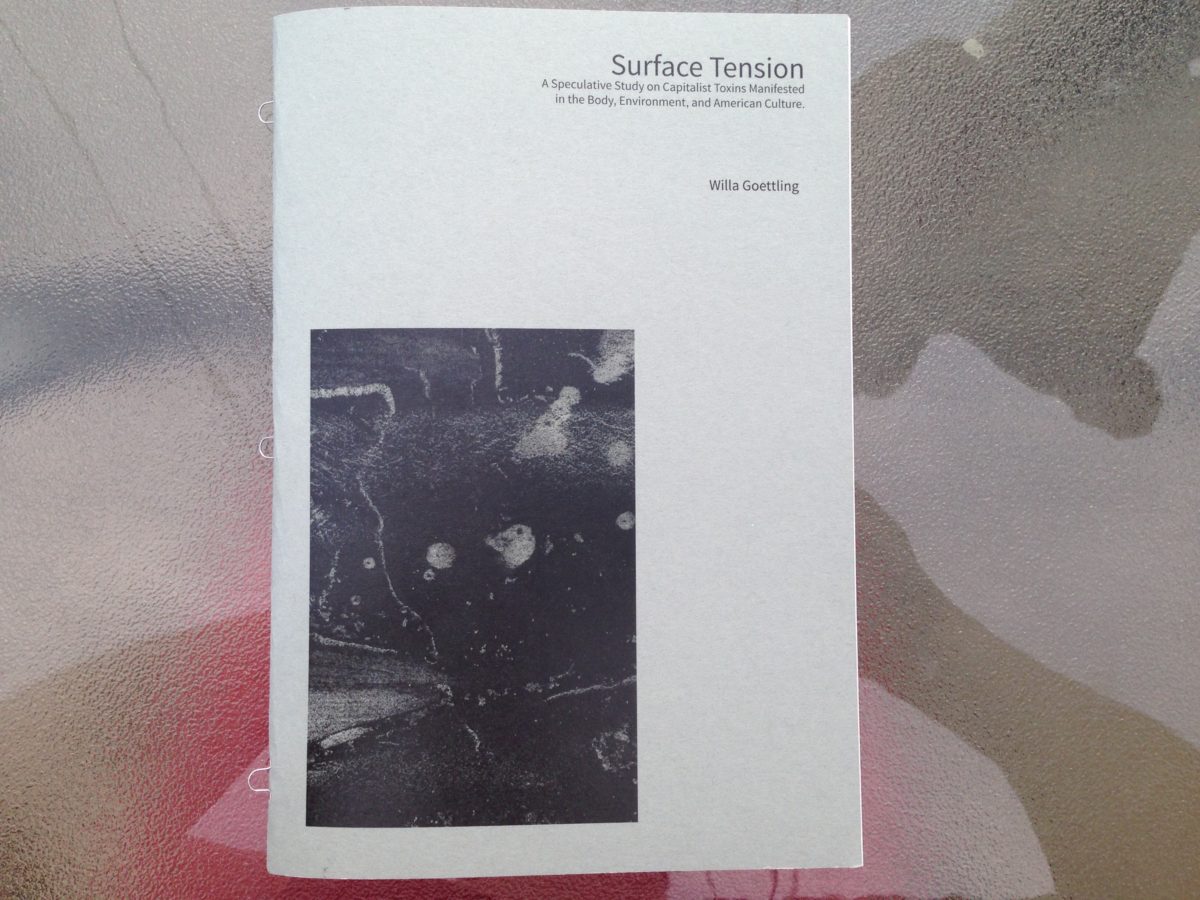

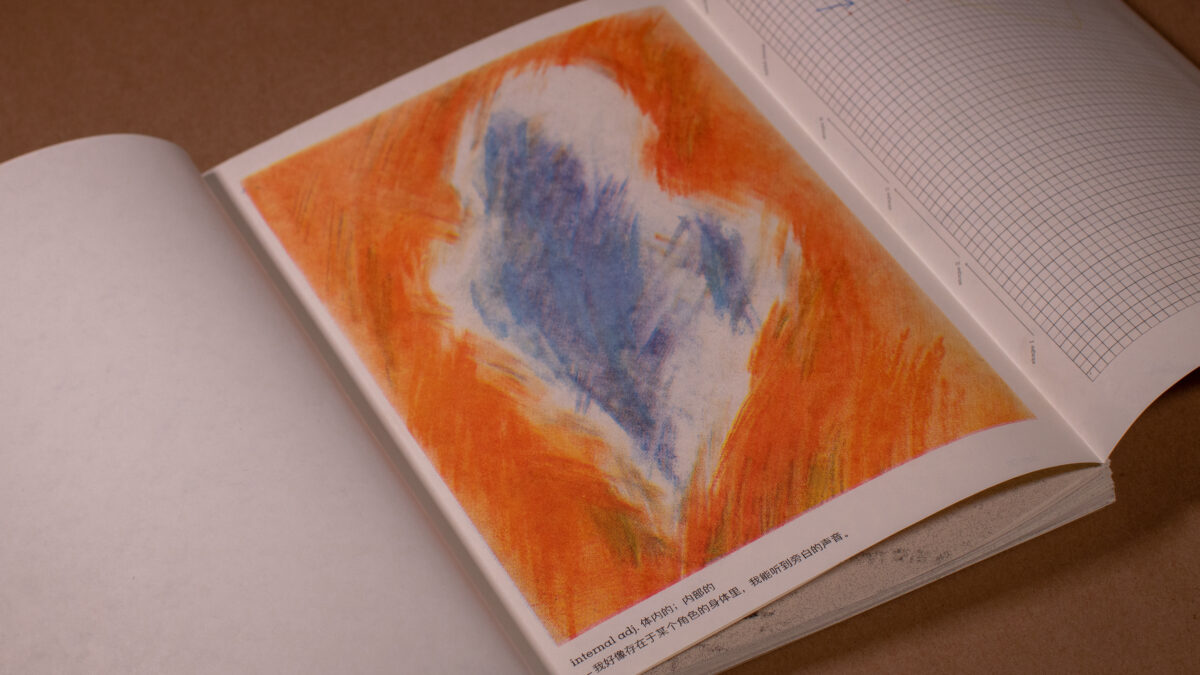

Image 2: “What adventure down there awaits its end?”, 2020 riso-printed book, 8 x 10 inches

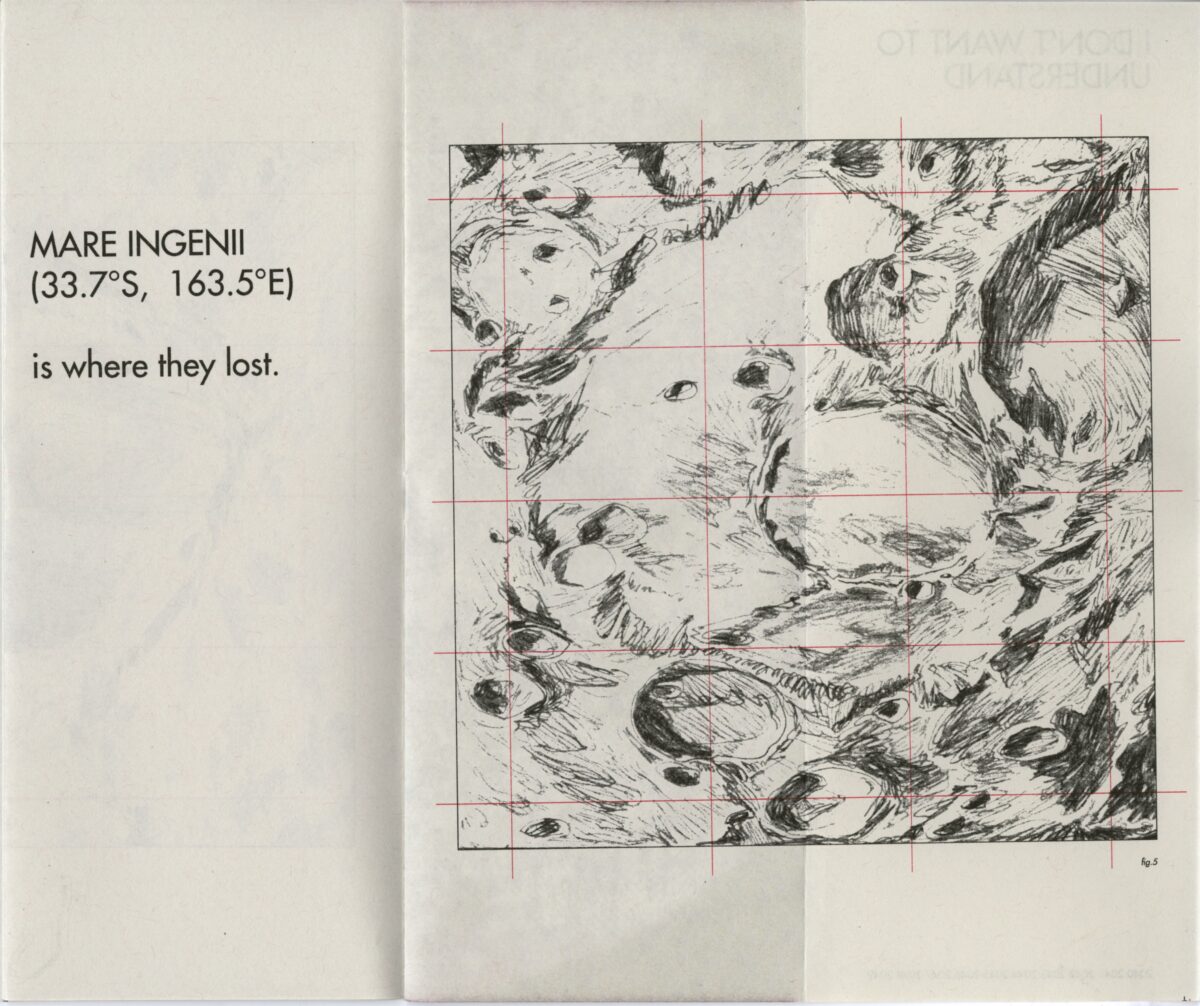

AY: So these sides are images of the dreams (see Image 1). And what are these on the other side (see Image 2)?

YW: It’s a full moon cycle. On the front is my bedsheet and on the back is the moon phase on that day. And if you unfold it, the image of the dream is inside. I also included the weather of that day.

A: Oh and I also saw on your website you made a book about the moon? I really like that one.

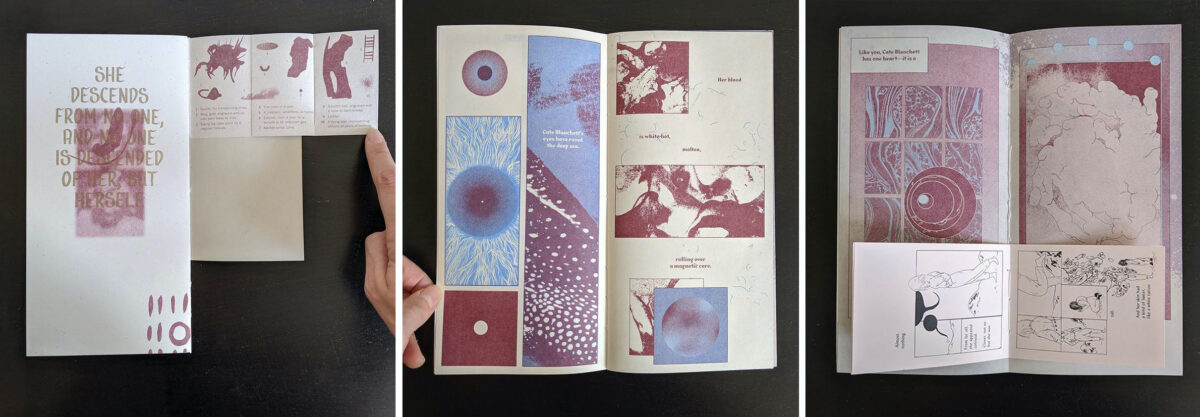

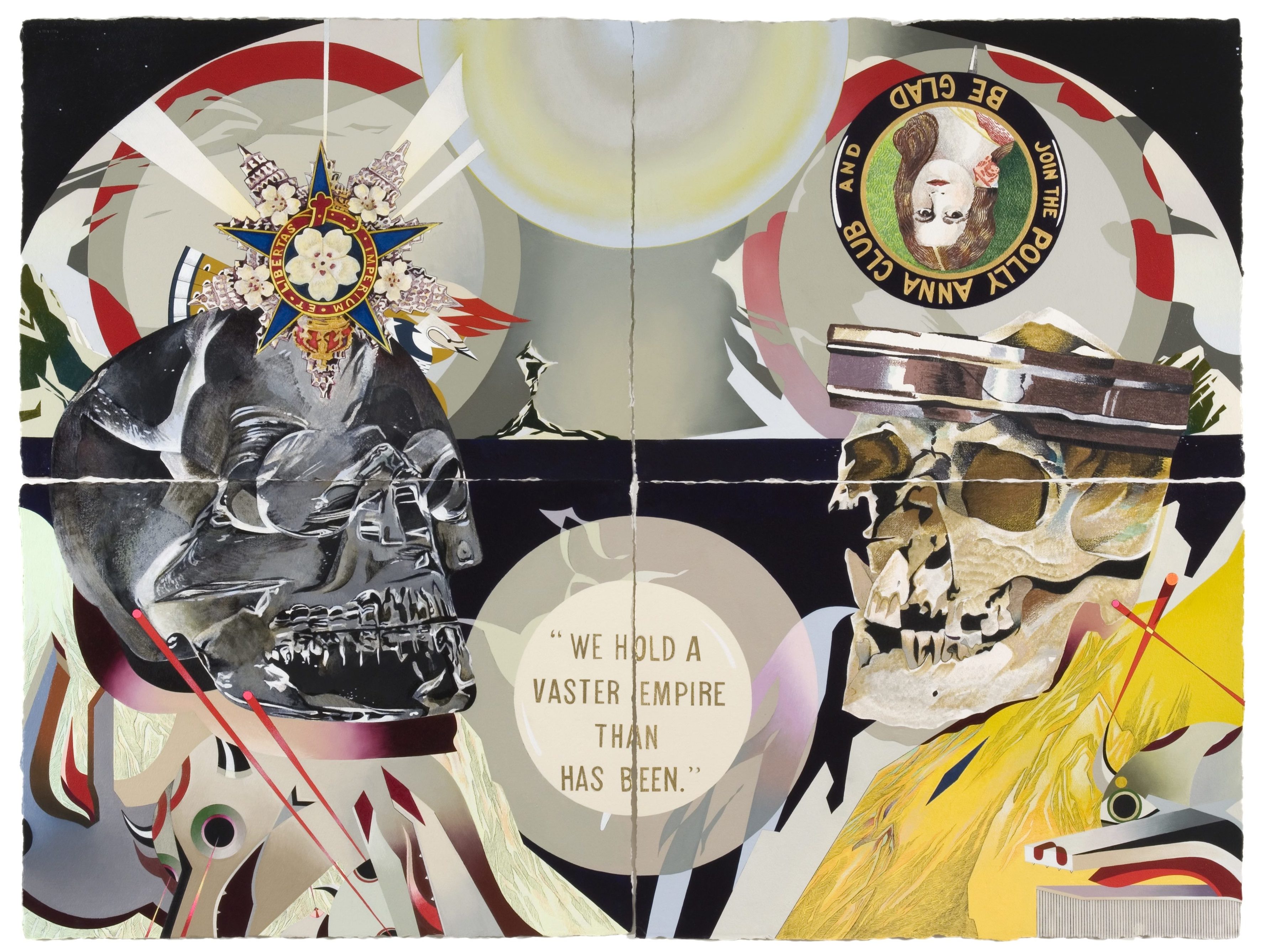

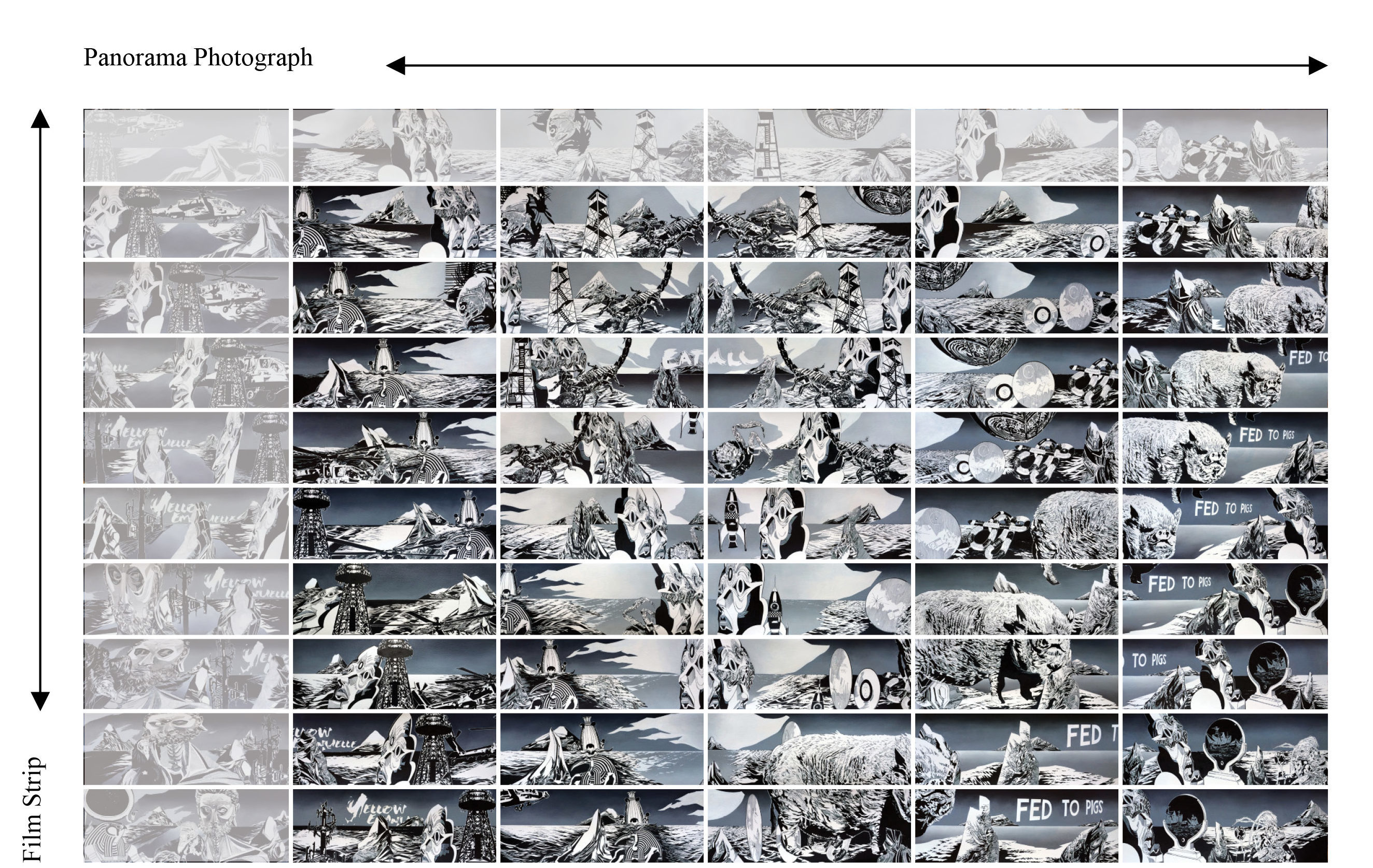

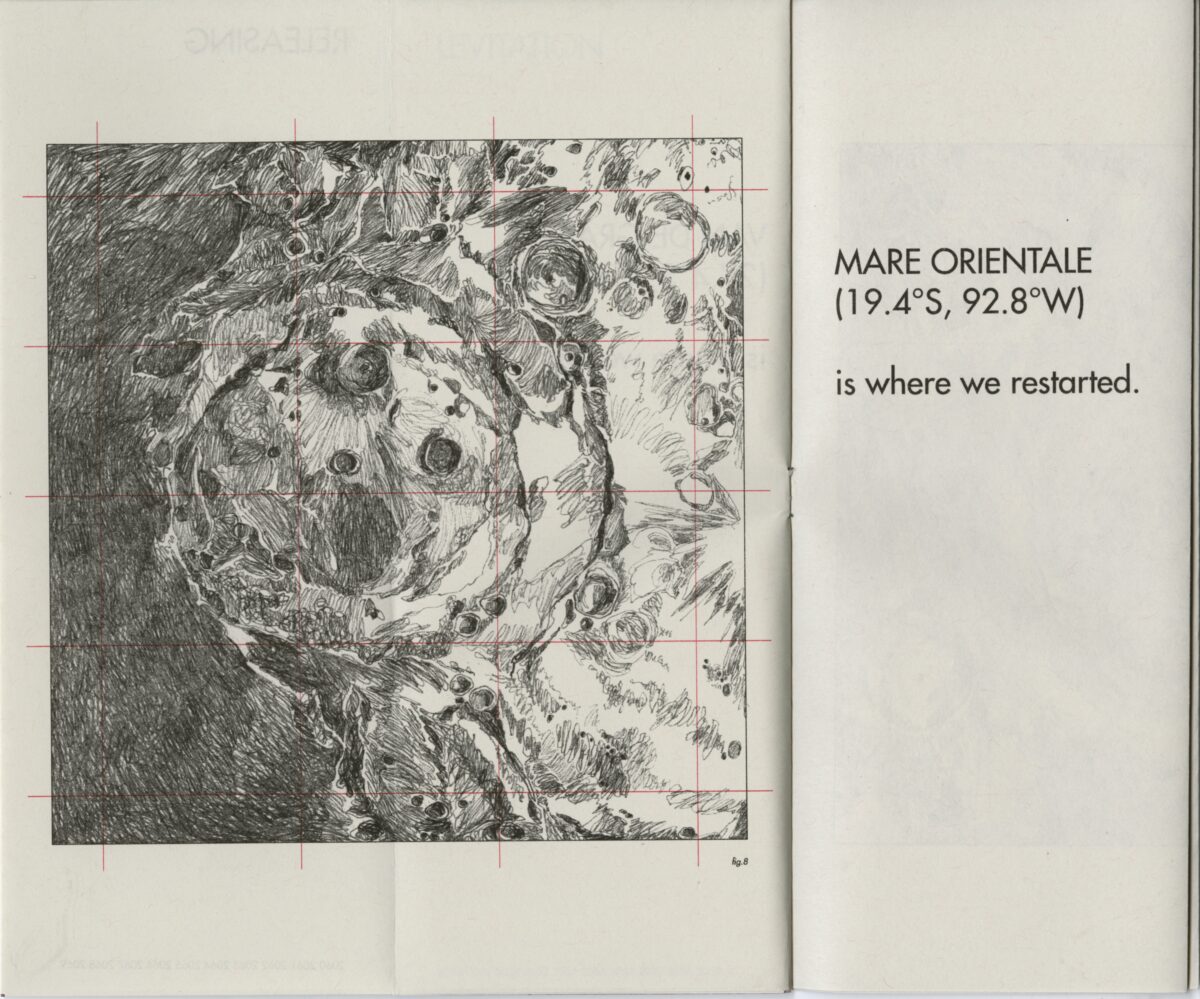

YW: Yes. The inspiration is from a class where we made a Whole Earth Catalog for 2070, so I made a fictional history timeline of the Moon from 2020 to 2070. The project was in the form of a scientific or archaeological report. I wrote the timeline from the perspective of people who migrated to the Moon and how they looked back to their history from 2070. I made this riso book based on that timeline.

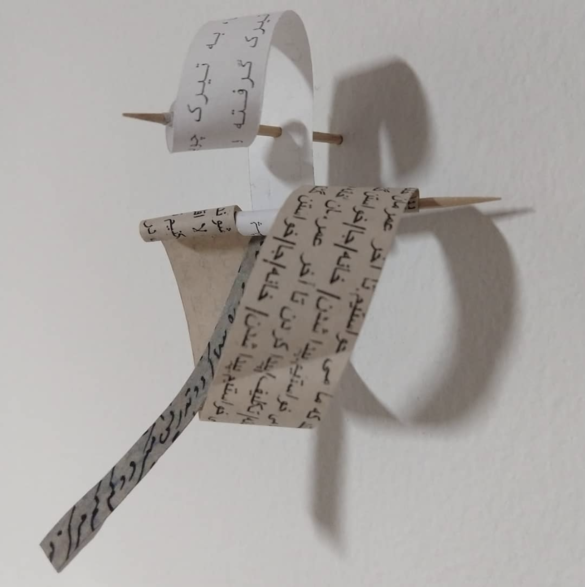

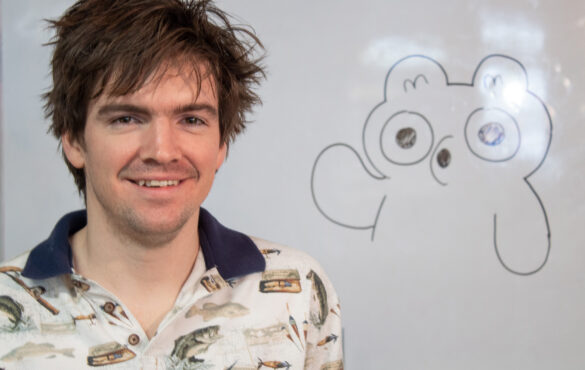

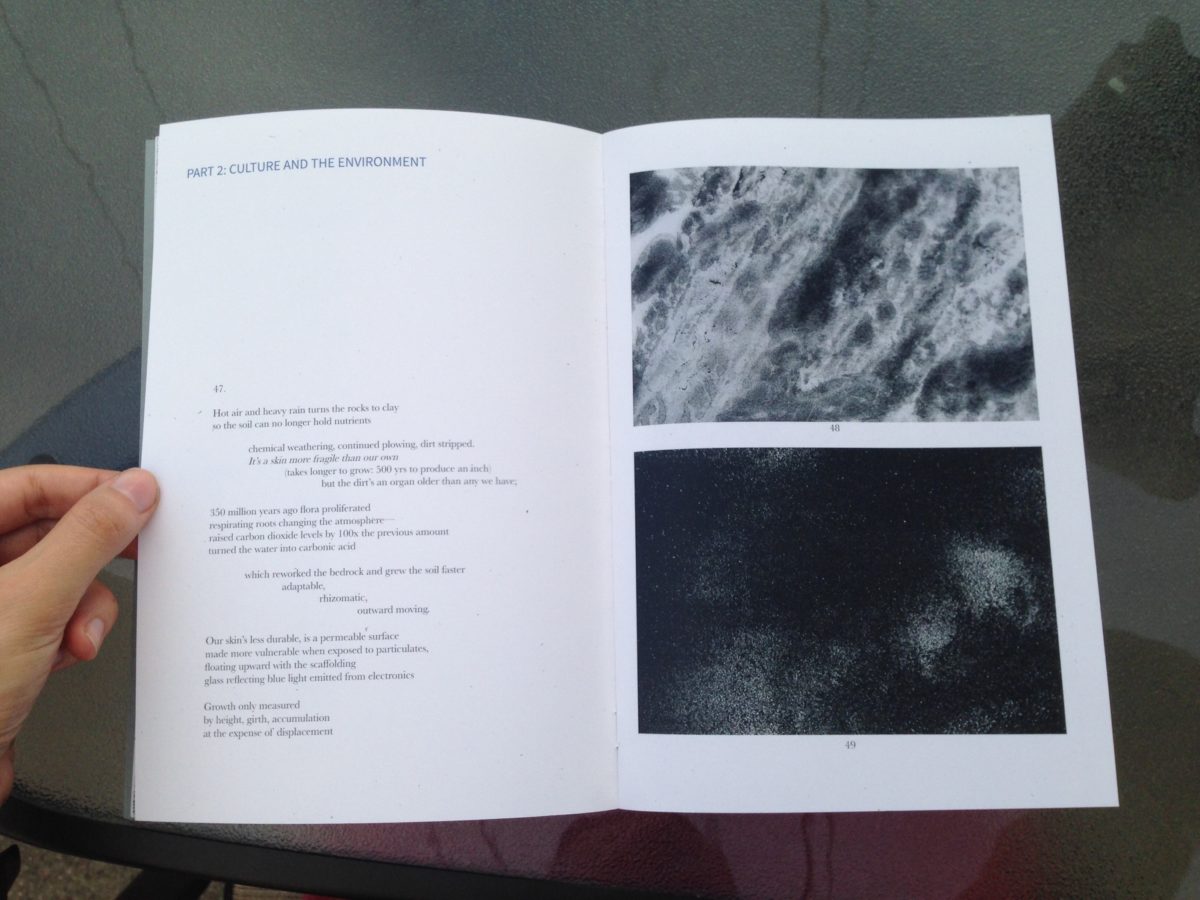

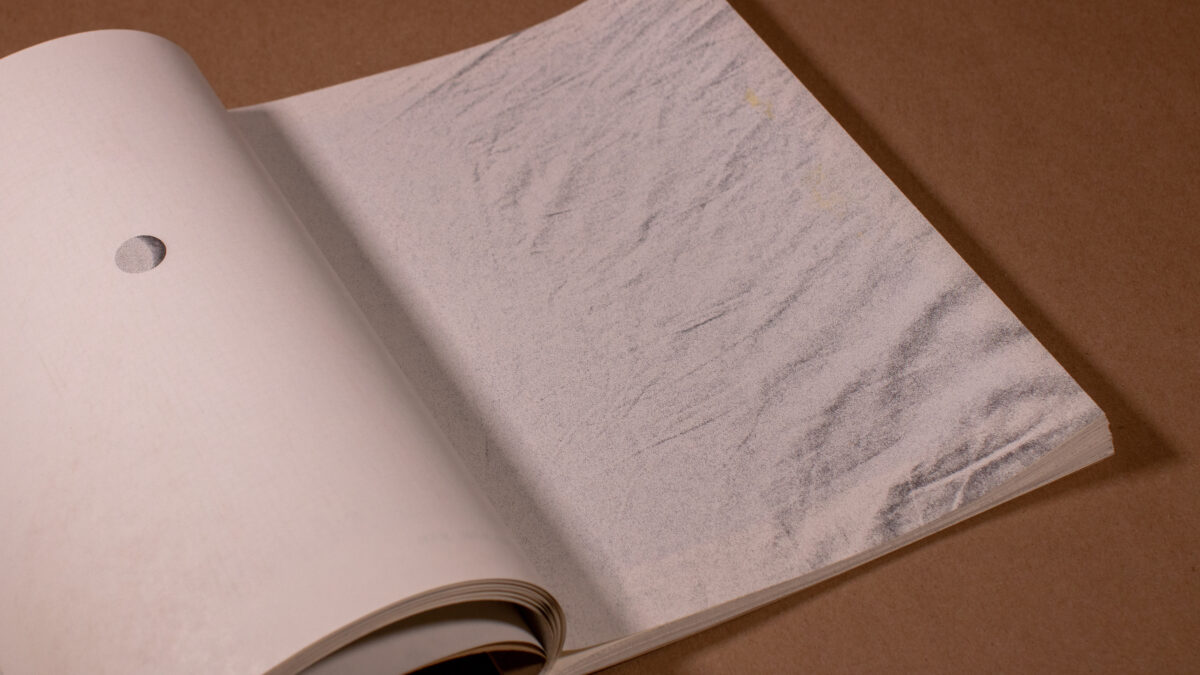

Image 3: “THE LUNAR ARCHIVE: 2020-2070”, 2021 riso-printed book, 4 x 10 inches

AY: Can you talk about the history timeline a bit more?

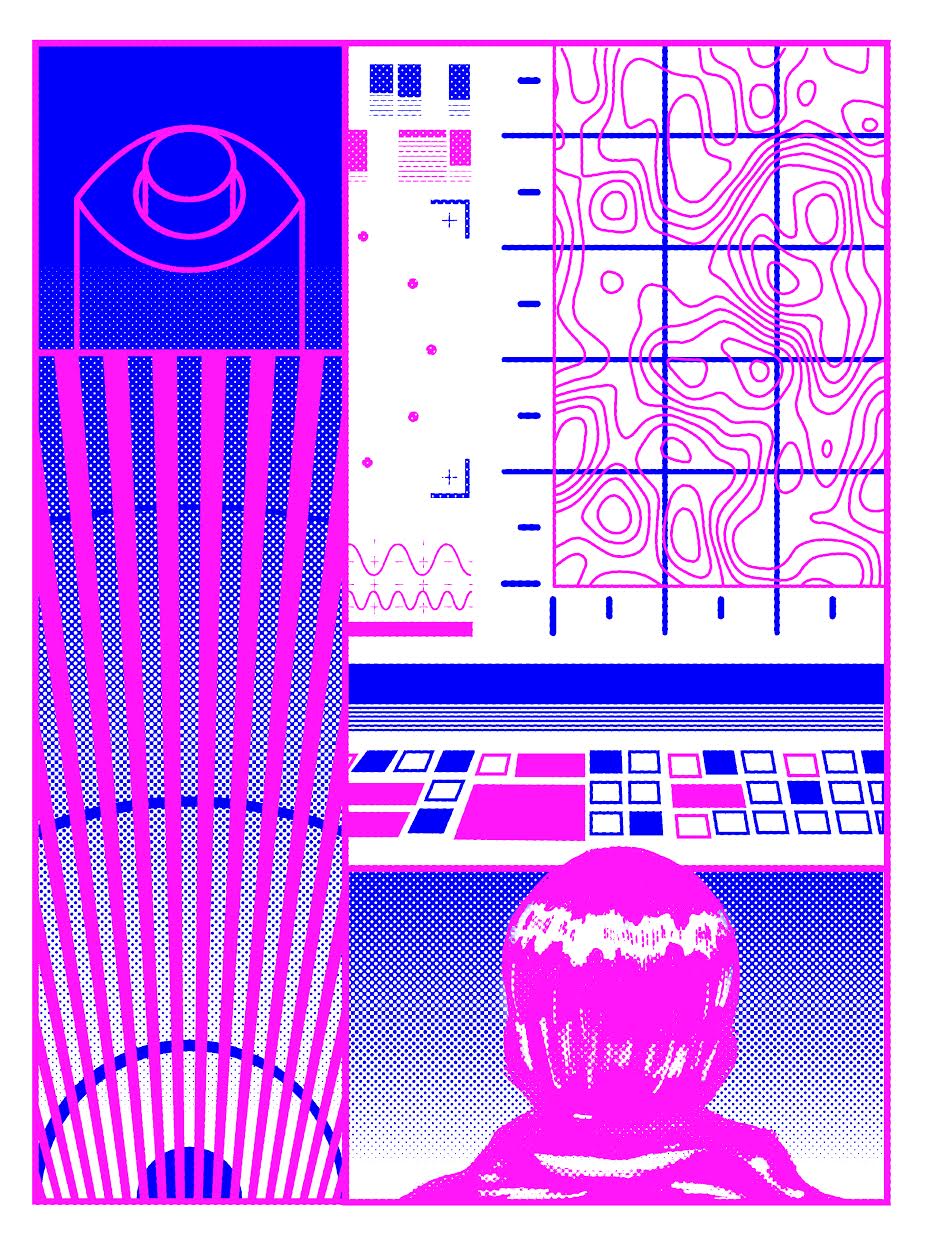

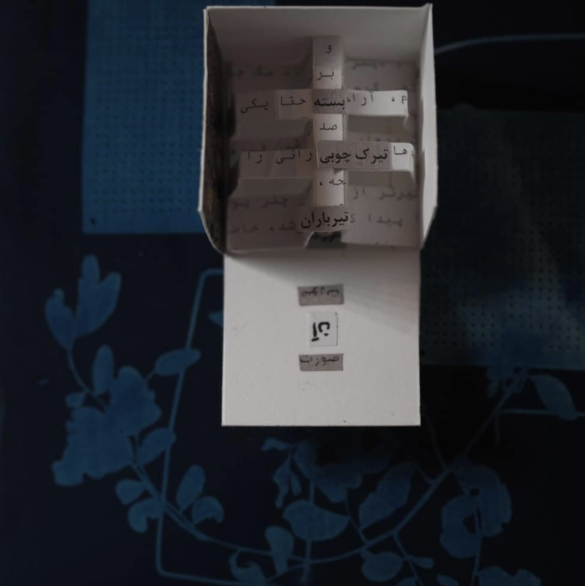

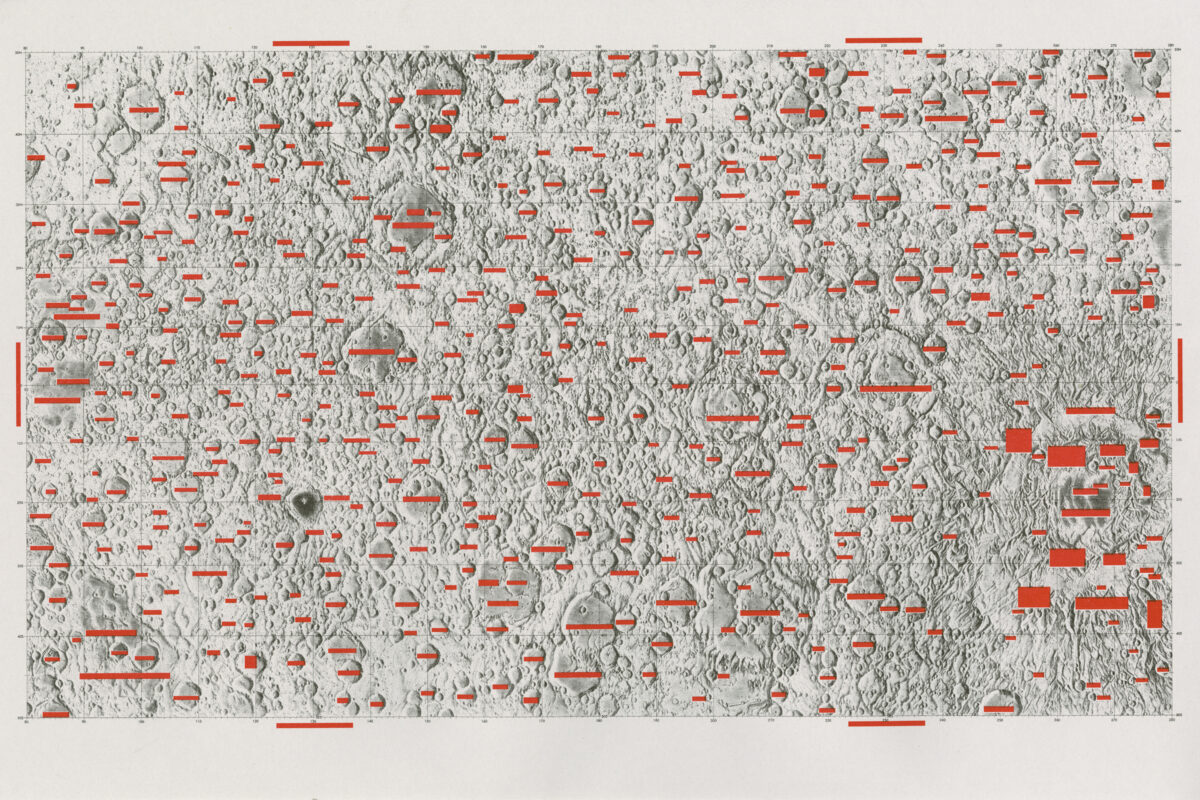

YW: It’s very vague. In 2020, humans began to immigrate and landed on the near side of the Moon. As time passed and people expanded toward the far side of the Moon, their connections and emotional attachment to the Earth faded. 2050 was the turning point when they reached a distance where the Earth-Moon system of communication was lost. This caused a shift in perspective. The history is written by people living on the Moon in 2070, so they identify with the Moon more than the Earth. They address the people on the Earth as “they” (see Image 4) and call themselves “we” (see image 5). But before 2050, the story is about them as people from the Earth. And when they completely lost contact with the Earth, it started the history of the people of the Moon.

Image 4: “THE LUNAR ARCHIVE: 2020-2070”, 2021 riso-printed book, 4 x 10 inches

Image 5: “THE LUNAR ARCHIVE: 2020-2070”, 2021 riso-printed book, 4 x 10 inches

AY: In real life, do you spend time looking at the Moon at night?

YW: Yeah. I like to browse through space news like the NASA website. I also drew the surface of the Moon as my drawing practice based on real craters. I wrote the whole narrative in 2019 and the book’s timeline starts in 2020. I also started to practice drawing the Moon’s surface in 2019. So when 2020 came, I decided to combine these separate works into a book that I finished in 2021. I recently read about a performance artist who talks about her piece as a dying project as she ages, and I find that so beautiful. I’m thinking about continuing this project and expanding it a little each year, until 2070. I’m still thinking about it.

AY: That sounds like a very long-term artist book project. What makes you use books often as a form of your art?

YW: Reading has been a habit for me since I was young so books are the most familiar medium to me. I like books because they do not give me the pressure found in other forms of communication. For example, our conversation right now requires an instant response, either through words or expressions. But that is not the case with books. You might read a book years ago and one day you think about it and you have some response to it. Books don’t blame you for anything. I feel comfortable when others look at my art through the form of a book. I think they probably feel comfortable, too.

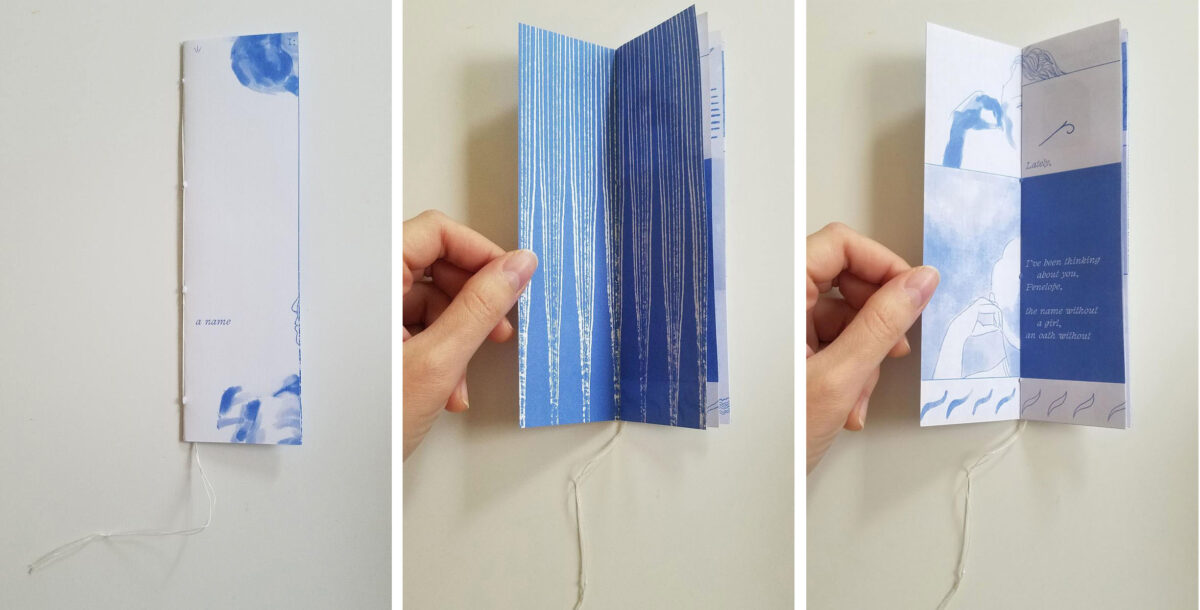

AY: How about texts? I find many bilingual elements in your books.

YW: Yes, I insist on doing bilingual pieces because the Chinese language is just beautiful. I don’t translate from one language to another in some of my books. There are some texts written in either English or Chinese only. I think this is a unique experience for bilingual readers because they can realize the subtle differences between the two languages. These differences are not because they got lost in translation. They were intended.

AY: This makes me think of the word “wandering” mentioned in both your bio and artist statement. There is a feeling of “wander” between the two languages since some words do not have direct translations. And if one can recognize the words in different languages, there are two spaces to land on and a seam in the middle that belongs to this person. Many of your previous books, including the one you made at Spudnik Press, were printed through riso. Are there particular reasons for this decision?

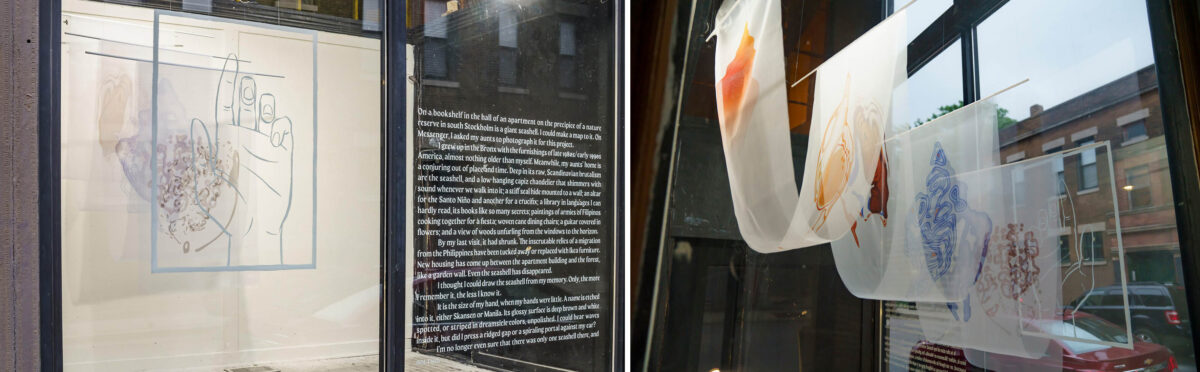

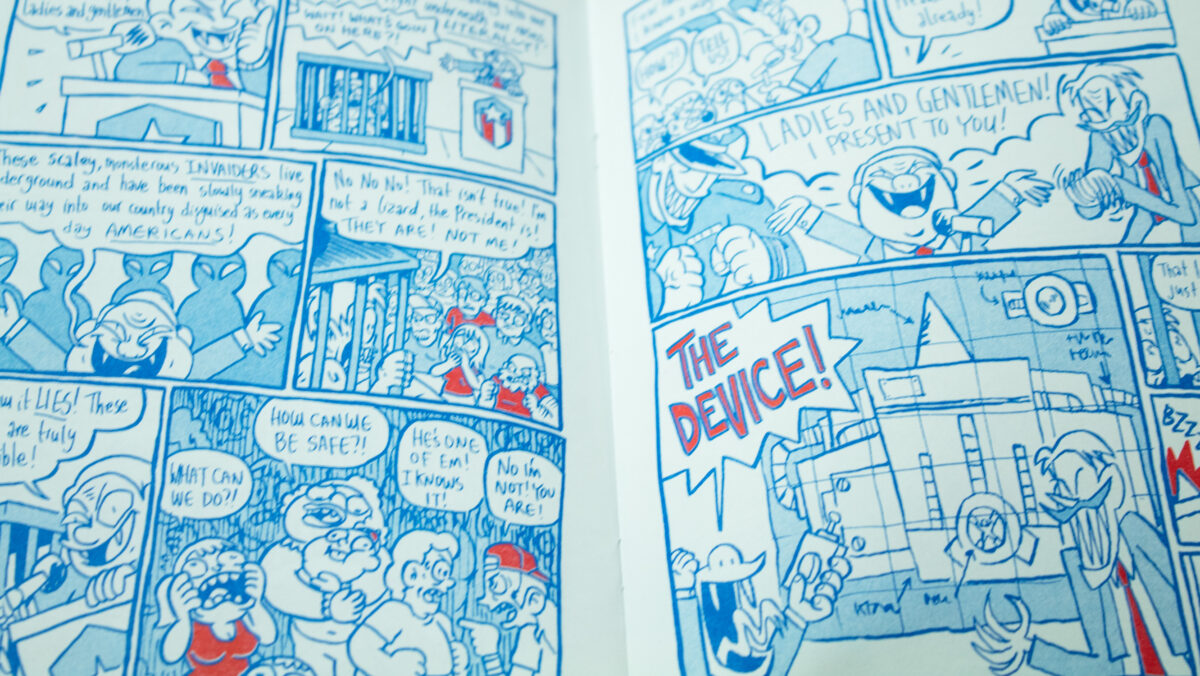

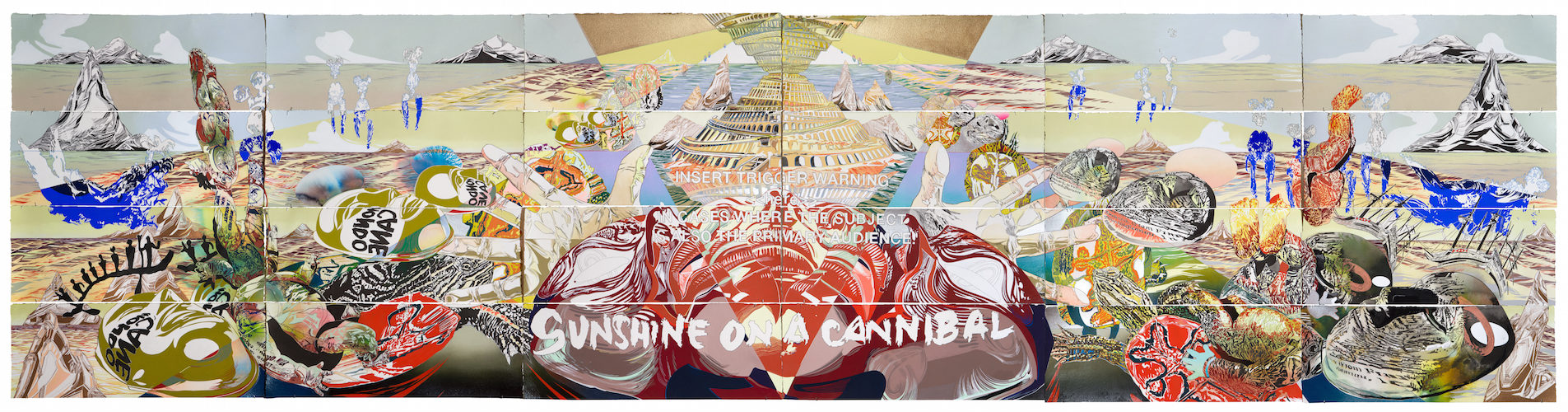

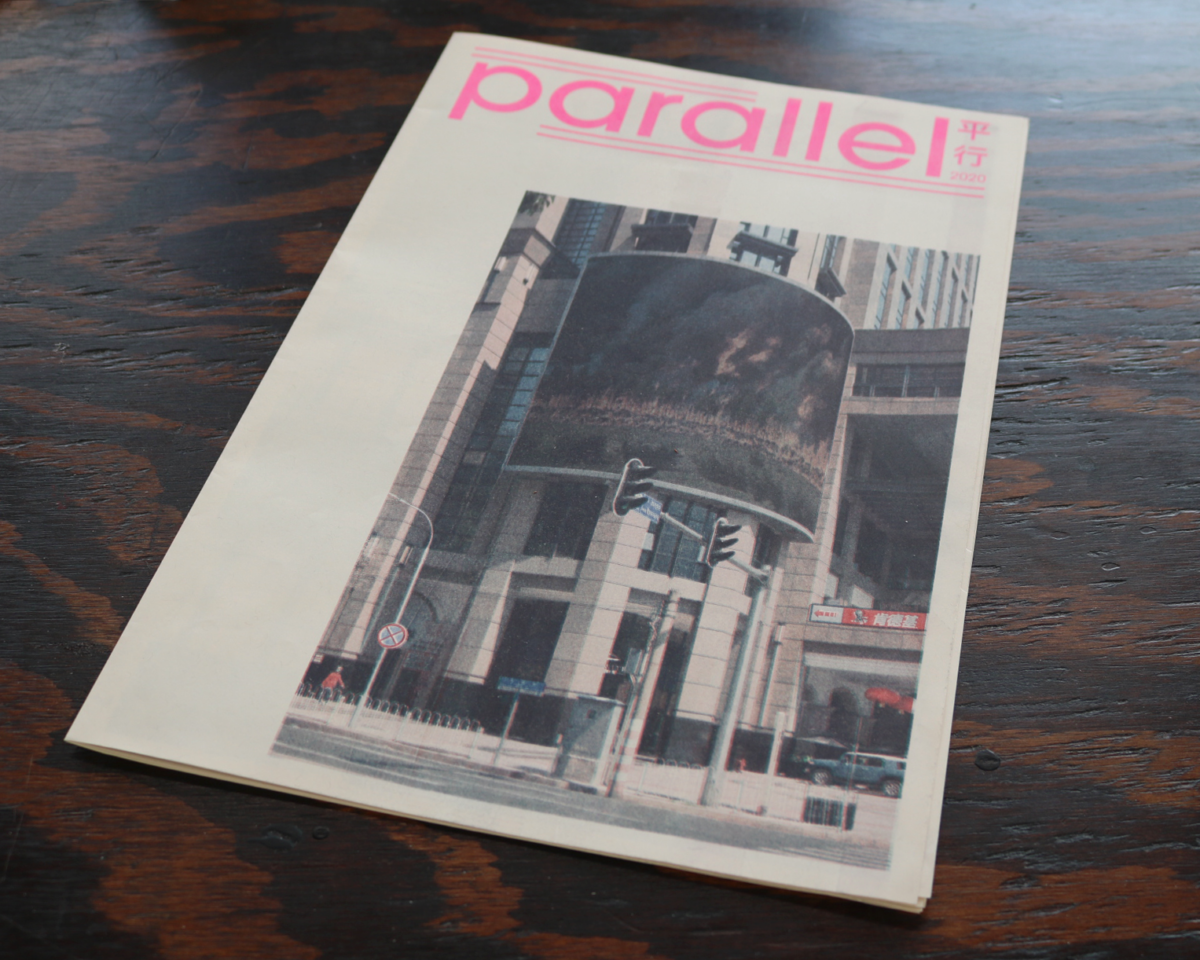

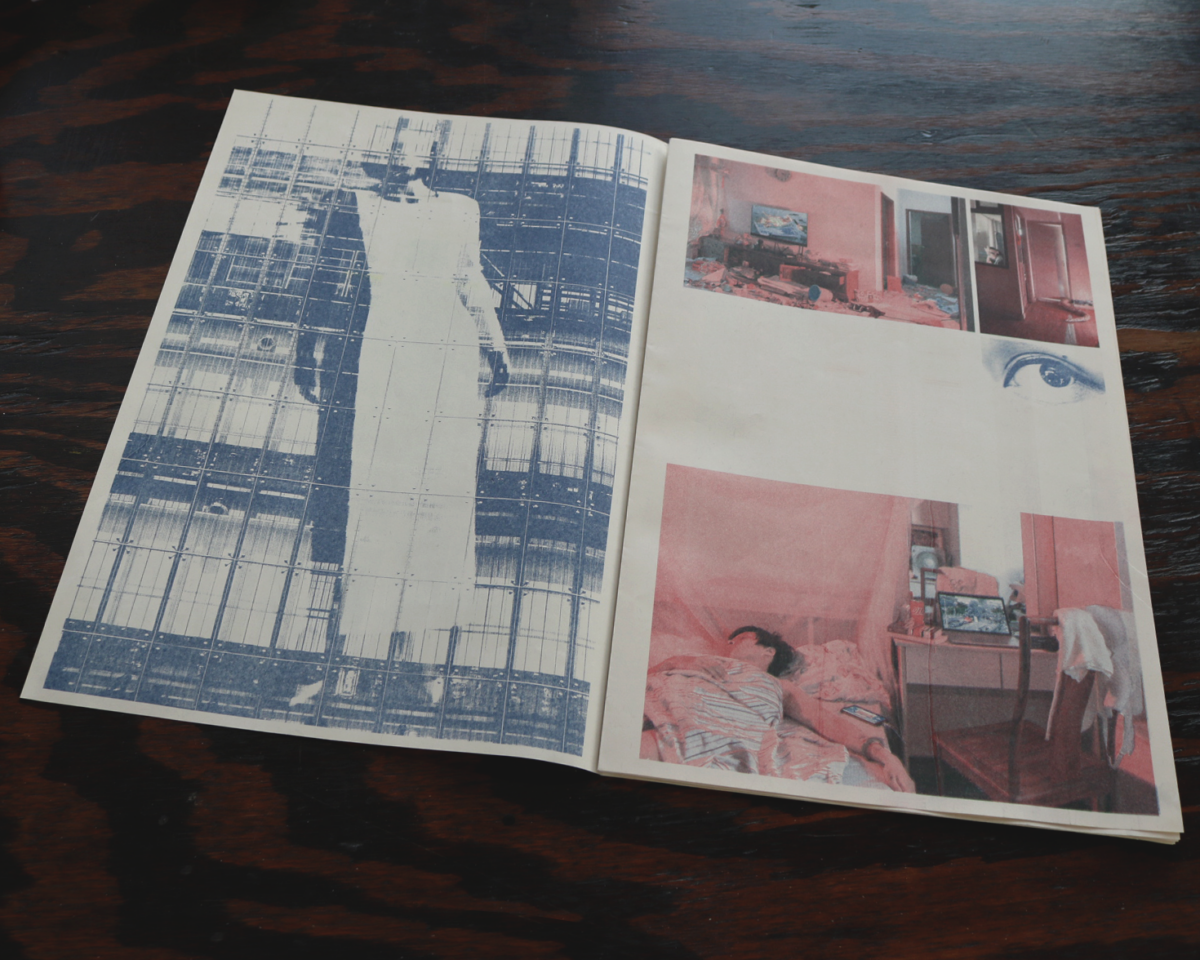

YW: With risography, I get to create the whole book completely on my own. The book I made at Spudnik is a collaborative work with my friend who’s a photographer. Risography gives me more control over the final outcome and I feel like I’m making something from the very beginning to the end. This year, I worked with my friend again to print a project called “Parallel” (see Images 6 and 7). It is currently on exhibit as part of my Fellowship at Spudnik Press now.

Image 6: “平行 parallel”, 2021 riso-printed newspaper, 10 x 16 inches

Image 7: “平行 parallel”, 2021 riso-printed newspaper, 10 x 16 inches

AY: What else did you do during the program? And how did you find out about Spudnik Press?

YW: During the process of application, I wrote a proposal for projects that I want to do during the eight months of Fellowship. We also did weekly monitoring shifts in the studio and attended seminars where we talked about things like teaching and writing for grants. We also had an exhibition for our public programming. My graduate advisor recommended Spudnik Press to me and I knew several students who went through Spudnik’s Fellowship Program before. After I graduated from SAIC, Spudnik became my working studio. I also sold some of my books here during the Hubbard Street Lofts 3rd Floor Market event last December.

AY: That sounds really nice! Where else do you sell or where else can we find your work?

YW: I have also sent my books to independent bookstores like Inga and Buddy in Chicago and Printed Matter in NYC. And I just concluded an exhibition on March 26 at the International Print Center in NYC as well.

AY: Since you recently wrapped up your Fellowship at Spudnik Press, what is next for you?

YW: I’m flying back to China this May. My friends and I are planning to build a private studio over there to continue making art. We are planning to set it up for screenprinting and risography for now. I will have the information about the studio on my website soon. I am also on Instagram at @by.yuwei.